Kubernetes at Work [Part 2]

This post describes how we run and manage karix.io on kubernetes, using helm for packaging and jenkins for CI/CD Summary

This post is part two (part 1) of a series of posts that describe how we built and now run karix.io. It covers the entire engineering effort undertaken and how and why we got here based on past learnings and experiences. It is my journey from a docker-compose PoC to kubernetes in production with the primary goal of improving developer/ops productivity and as a result ensuring a high uptime and quality of service for our customers.

Deployment

When I started working on karix.io 2 years ago, we were to build a global self-service API platform for two way messaging. We decided to run our services on containers. Once we did that we on the architecture, deciding on what microservices to build to ensure we had, isolated and independently scalable components for separate functions like authentication, billing, routing etc.

At the time, we were only two engineers working on this. The thought process was to make sure that most developer time is spent on building the service and not managing infrastructure. Also to build a system which would ensure super simple onboarding of new developers as the team grew.

Any SaaS product has to start with the build pipeline. This is the core unit around which all software releases should revolve. The way I think about pipelines is from these 3 perspectives.

Fast Deployments

The time gap between creating a release tag and having your release run in production should be optimised. This becomes all the more critical in case of hotfixes. Ideally this scenario should never occur, and bugs need to get caught either in your test cases or in staging when running integration suites. But in situations where buggy code does get deployed to production, we should be able to deploy a working release as soon as possible without much delay. Your pipeline should not be a bottleneck there.

Debugging Failures

In the event a build fails, a developer should be able to debug the build and figure out the exact issue with either their code or the build script. This should be notified early on during the build process. Certain notifications to do with container building, packaging and pushing the packages to our storage need to be notified then and there as it happens..

Immutable Builds

Builds need to be immutable. What I mean by this is when a release gets tagged, new changes in code cannot be pushed using the same tag. Having your release tags and builds immutable, lets you get your cluster in the state you wish to have it in at any point in time.

With these requirements established, we choose Jenkins. I think Jenkins is the most versatile tool out there and can be shaped based on your needs. Pipeline provides an extensible set of tools for modeling delivery pipelines “as code” via the Pipeline DSL. This means that your code is now shipped with instructions on how it is supposed to be built. And this turns the whole concept and ideas behind dev-ops into reality. Your developers are able to define how a particular service will be built, how to run test cases, where to find config files for an environment and how to package it for deployment. It enables your developers to make these decisions as part of their code.

So we came up with a golden rule in our team. Every code component on our platform has to have these 3 files.

-

Dockerfile

-

Makefile

-

Jenkinsfile

We also have a folder called charts which is checked-in with the code. I’ll come back to this later in the post.

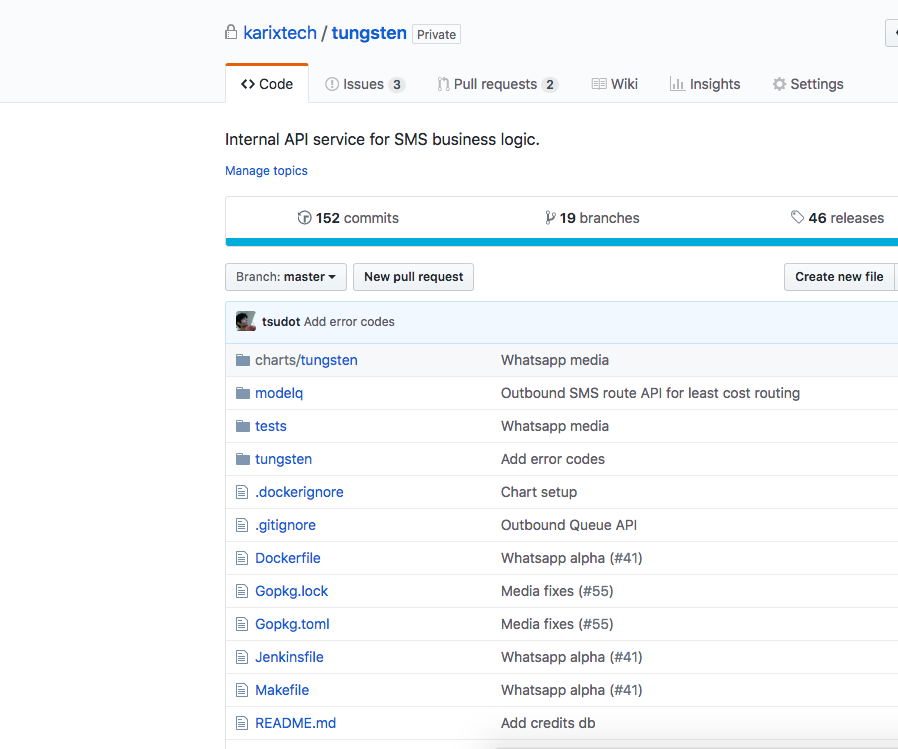

We’ll look at these files from our internal service called tungsten. Tungsten is responsible for fetching routes for our communication channels. It is also one of the main layers of our messaging architecture.

The Dockerfile specifies how to build the container. This is mostly generic across projects of a particular language. One pro-tip: If you are using containers in production, always build the base image yourself. Using public base images puts you at a high security risk.

The Makefile has standard targets for compiling, building and running tests. These standard targets are defined so that very little change is needed in your build script. A Jenkinsfile can be used generically across different repositories.

The Jenkinsfile is written in groovy. It calls the standard Makefile targets and has logic to upload the builds to a repository. We also have logic here to create deployment packages for various environments.

We run Jenkins on kubernetes and each build is spawned in its own Pod using the jenkins-slave container image. So when a build is triggered, Jenkins will spawn a new slave Pod, run the instructions in there and will terminate the Pod when the job finishes. We achieve this by using the kubernetes-plugin. This plugin creates a Kubernetes Pod for each agent that is started.

We use semver to create release tags to trigger builds. Patch versions will get deployed on staging. Minor and major version are production builds to be deployed on the production cluster. When a release tag is created, we’ve configured Jenkins to automatically start the build. It will look for a Jenkinfile in the repository and start the build process. The release tag is used as the version for this build.

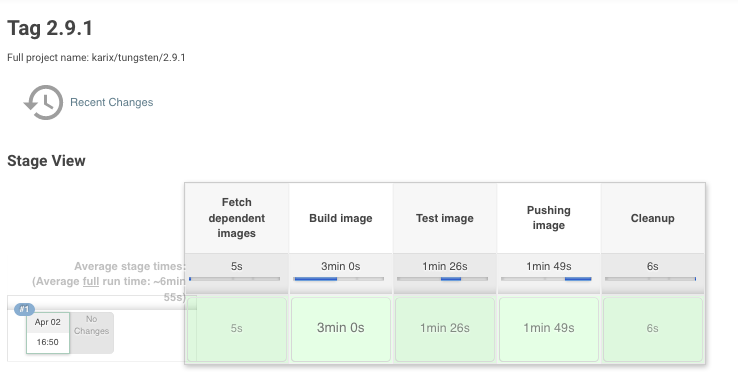

Our build is split into different stages, this helps us debug build failures better.

The first stage is to fetch dependent images, so for tungsten, which is a golang project, we will fetch the base golang image.

We build the tungsten source code next. We also build the postgres image which will be connected on the same network as tungsten in the next stage to run test cases.

The third stage is to test the image. If test cases pass, we will push the image to our registry and create a versioned deployment package. We use helm for packaging, and I’ll come to that when I talk about deployment.

Packaging

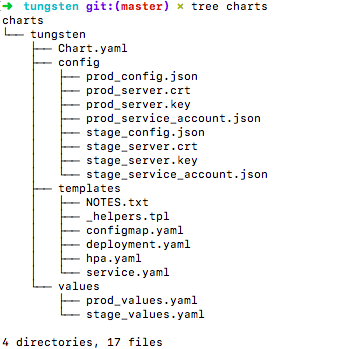

Currently we create builds for 2 environments, staging and production. The Jenkinsfile uses the charts folder to build a helm package. The charts folder has templates which will spew out kubernetes object configurations.

This is what the charts folder looks like. The templates folder contains different set of files to generate a deployment, service and a configmap.

Let’s start with the k8s Configmap template. The config file mounted to the docker image varies based on the environment we are building for. Currently we store all config files in the repository itself, since it is easy to manage. We need a better plan to handle this though, since scaling to multiple environments is not feasible with this approach. The configmap is given a name which is the release name. It has data files, the location of these files are specified in the values.yml (the files are checked in to the repository) and these files will eventually be mounted to the container through the Configmap in the Deployment object.

The deployment object gets generated based on the values passed to it. The Deployment will have the config files mounted to the container which is fetched from the Configmap. Environment variables can also be passed to the container, we mostly pass variables specific to the environment the deployment runs in, along with credentials the container needs to boot up or access the database. The spec also has Readiness and Liveness checks based on which the deployment gets marked good to serve traffic. These checks are usually exposed over TCP or HTTP by your containers.

Next is the Service object. This object is used to route traffic to your Pod. A service will have a pod selector which will describe where to route the traffic to. It has an external port which the service will open to accept incoming traffic and a target port, which the service will use to route the traffic to. The target port is the one your Docker container exposes.

The last object in this repository is the HPA. Think of this as your auto scaling spec. It sits on top of your deployment and scales your deployments based on the spec.

All of these files are generated based on the values we pass into it in the form of values.yml. Having separate values lets you create kubernetes object files for different environments.

Once we have all of these object specs generated, we will use helm to package these files into a tgz for deployment on the cluster.

This tar get pushed to our chart repository as a versioned unit. We use chartmuseum as our chart repository.

Follow up posts in this series will describe how we use helm for packaging kubernetes components, our emphasis on the importance of testing, our tooling for releases/deployments and our take on best practices like monitoring, alerting etc along with future goals. Thanks for reading and stay tuned!